Re Ian Bremmer 'Could third-party candidates upend the 2024 US election?' 3 April The current political movement in the USA…

One Laptop Per Child (OLPC) – bad news & good news

Written by Diana Thebaud Nicholson // December 10, 2012 // Education, Science & Technology // 2 Comments

2012

10 December

Google makes MIT professor’s dream of “$100 laptop” a reality

(Reuters) – Google Inc began selling basic laptop computers to schools at a price of $99, meeting a price point that prominent MIT professor Nicholas Negroponte famously held out in 2005 as key to bringing computing power to the masses.

The Internet giant said on Monday that it will be offering the steep educational discount on Series 5 Chromebooks from Samsung Electronics Co through December 21. They typically retail for $249.

Negroponte’s One Laptop Per Child Foundation failed to meet his ambitious target, which critics said would be impossible to meet when he set it. His XO laptop currently sell for about $200.

Still, he is widely credited with helping to launch the era of low-cost portable computing.

30 October

Ethiopian kids hack OLPCs in 5 months with zero instruction

Here’s what happened as related by OLPC founder Nicholas Negroponte at MIT Technology Review’s EmTech conference last week:

We left the boxes in the village. Closed. Taped shut. No instruction, no human being. I thought, the kids will play with the boxes! Within four minutes, one kid not only opened the box, but found the on/off switch. He’d never seen an on/off switch. He powered it up. Within five days, they were using 47 apps per child per day. Within two weeks, they were singing ABC songs [in English] in the village. And within five months, they had hacked Android. Some idiot in our organization or in the Media Lab had disabled the camera! And they figured out it had a camera, and they hacked Android.

This experiment began earlier this year, and what OLPC really want to see is whether these kids can learn to read and write in English. Around the world, there are something like 100,000,000 kids who don’t even make it to first grade, simply because there are not only no schools, but very few literate adults, and if it turns out that for the cost of a tablet all of these kids can simply teach themselves, it has huge implications for education. And it goes beyond the kids, too, since previous OLPC studies have shown that kids will use their computers to teach their parents to read and write as well, which is incredibly amazing and awesome.

9 April

The Failure of One Laptop Per Child

“25 million laptops later,” Mashable announced today, “One Laptop Per Child doesn’t increase test scores.” “Error Message,” reads the headline from The Economist: “A disappointing return from an investment in computing.”

The tenor of these stories feels like a grand “Gotcha!” for ed-tech: It’s shiny stuff, sure, but it offers no measurable gains in “student achievement.” So while the OLPC project might have been a good idea, so the story goes, it is not a good investment.

One Laptop Per Child was a good idea, a noble and ambitious one at that. Originally proposed in 2006, OLPC aimed to build an inexpensive laptop that would be sold to governments in the developing world and made available in turn to the children in those countries via their respective ministries of education. Easier said than done. Over the course of the past 6 years, the OLPC has fussed with hardware and software specs, finally building a laptop (and now, a tablet) that costs $200 (twice that of the originally promised price).

In the meantime, much of the developing world has experienced its own mobile computing revolution. There are now a number of manufacturers working on low-cost devices for that market. There’s the Intel Classmates PC, for example (with similar hardware, but more expensive software than its OLPC coursin); there’s the Worldreader project (it delivers villages a library full of e-books via Kindles); and there’s the now-infamous Aakash tablet (which was sold in India for $35 but with its reliability and functionality very much in question).

7 April 2012

Error message — A disappointing return from an investment in computing

(The Economist) GIVING a child a computer does not seem to turn him or her into a future Bill Gates—indeed it does not accomplish anything in particular. That is the conclusion from Peru, site of the largest single programme involving One Laptop per Child, an American charity with backers from the computer industry and which is active in more than 30 developing countries around the world.

Peru is enjoying an economic boom, but has one of Latin America’s worst education systems.

Part of the problem is that students learn faster than many of their teachers, according to Lily Miranda, who runs a computer lab at a state school in San Borja, a middle-class area of Lima. Sandro Marcone, who is in charge of educational technologies at the ministry, agrees. “If teachers are telling kids to turn on computers and copy what is being written on the blackboard, then we have invested in expensive notebooks,” he said. It certainly looks like that.

2008

30 September

Venezuela orders one million laptops for schoolchildren

Venezuela is ordering one million low cost laptops for its school children.

The machines will be based on the Intel Classmate laptop that has been designed for school children.

Many see the deal as a blow for the One Laptop Per Child organisation that has also been touting its child-friendly machine to developing nations.

11 June

65,000 computers for Colombian schoolchildren (Full text in Spanish only)

An agreement signed between Colombia and the OLPC Foundation will provide 65,000 schoolchildren with laptops.

4 January 2008

It grieves us to see The Economist’s review of one of our favorite development projects, but we take heart in the conclusion that “Mr. Negroponte’s vision for a $100 laptop was not the right computer, only the right price. Like many pioneers, he laid a path for others to follow.”

One clunky laptop per child

From Economist.com

Great idea. Shame about the mediocre computer

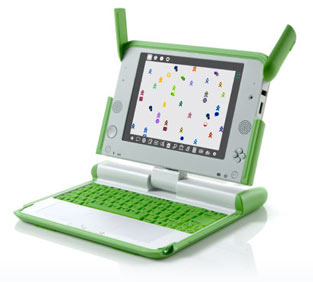

IT WOULD be a stunt, but one perhaps worth performing, to write this column on the tiny, green and white, $200 XO computer from One Laptop Per Child (OLPC) that sits idle before your columnist. Alas, he cannot.

This is not because the keys are too small for his adult hands (though they are), or because the processor’s slow speed makes the machine frustrating to use(though it does). Nor is it because the track pad sometimes goes screwy and the keys lack the normal pressed-key response that allows smooth typing. It isn’t even because moving the column from the word-processing application to the web-mail system is prohibitively difficult.

Instead, it is because the XO, which your columnist has explored since it arrived a few days before Christmas, has bugs that cause occasional crashes. A discreet message sometimes flashes when the system boots up, warning of some sort of data-check error. This, along with the host of other hiccups, necessitated the use of an ordinary, expensive computer for this column.

It wasn’t supposed to be this way. When Nicholas Negroponte, a tech guru at the celebrated Media Lab at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, launched the initiative in 2005, the vision was grandiose, but the implementation seemed beguilingly simple. Computer-processing technology had become so widespread and inexpensive that DVD players and mobile phones had as much power as the PCs of just a few years ago. Just add a screen and keyboard, the thought went, and you’ll have a cheap, functional laptop.

Indeed, Mr Negroponte’s vision was brilliant. He planned to blanket the developing world with tens of millions of $100 laptops for kids. The low cost would come from a tripartite “perfect storm”. First, economies of scale: sales would be directly to governments, who could only buy quantities above 1m. Second, the machines would bypass Intel’s processors and Microsoft’s software in favour of open-source stuff. Third, commodity parts would keep the price low.

Mr Negroponte sought funding from education ministries: “It’s an education project, not a technology project,” he was fond of saying. Faced with critics who argued he should concentrate on the classic development issues that keep people poor and sick rather than doling out high-tech gear, Mr Negroponte would rightly reply that education through computers can help resolve all such problems.

Today that optimism seems Pollyannaish. Many governments (including Nigeria’s and Libya’s) cancelled their informal commitments to purchase the machines when they realised the devices were untried, the price higher than envisaged and other cheap laptops available.

A few trials in places like Haiti and Rwanda, together with orders from Peru and Uruguay collectively fell far short of even 1m machines. A clever holiday promotion in North America that offered two laptops—one for the buyer and one to donate to a child in a developing country—for $399 similarly fizzled. Production lines at Quanta Computer, a Taiwanese manufacturer, were left idle.

All this is a shame, not least because Mr Negroponte’s idea was sound and the machines’ hardware, at least on paper, impressive. The initiative inspired several advances in laptop technology, in terms of features (flash memory instead of a spinning hard-drive), design (a laptop-to-tablet form and a waterproof keyboard) and price reductions. A pull-cord hand-generator for power is in the works. OLPC and their boosters deserve hearty congratulations for all of this. Unfortunately, OLPC’s problems, which can be distilled into four main areas, risk turning a wonderful idea into a plastic paperweight.

First, the implementation of the technologies is terrible. In their zeal to rewrite the rules of computing for first-time users, OLPC shipped machines with a cumbersome operating system. For example, adding Flash to do something like watch a YouTube video requires users to go into a terminal line-code and type a long internet address to download the software: it seems impossible to cut-and-paste the address. Major PC vendors spend millions in research and development to enhance a computer’s usability; OLPC tried to reinvent the wheel and came up with an oval.

Second, the go-to-market execution (as it’s called in the industry) was imperfect. There was a lack of documentation, support and methods to integrate the PCs into school curricula, teacher training, and the like. OLPC seemed to think that just by handing out laptops, everything would sort itself out. This columnist happens rather to like that gung-ho approach, yet also recognises that the consumer is not the nine-year-old user with infinite time on her hands, but a government bureaucrat who has to evaluate the machines relative to the other options.

That leads to the third problem. Since the project launched in 2005, commercial rivals have emerged: Intel’s “Classmate” at around $250; Acer’s laptop at $350; Everex PCs with Zonbu software at around $280; Asustek Computer’s Asus Eee at under $400; and an Indian competitor, Novatium Solutions, which created a basic “NetPC” for around $80. There are many more.

OLPC initially treated all these activities as threats rather than competitors. Lately, Intel has supported OLPC, though this week said it would leave its board, and Microsoft is trying to tweak Windows XP, an earlier operating system, to work on the XO. But all computer buyers will have to compare the XP to a lot of other products in the market—something that never seemed to have struck OLPC’s staffers as a possibility, but should have.

This leads to the final problem that has done the most to disappoint OLPC’s fans: the hubris, arrogance and occasional self-righteousness of OLPC workers. They treated all criticism as enemy fire to be deflected and quashed rather than considered and possibly taken on board. Overcoming this will be essential if the project is to succeed past its first release. Technology products improve based on user feedback. The OLPC staff will need to learn to listen to the candid criticism of outsiders for the second-generation of the laptop—or they do not deserve to build one.

Ultimately the OLPC initiative will be remembered less for what it produced than the products it spawned. The initiative is like running the four-minute mile: no one could do it, until someone actually did it. Then many people did.

Likewise, an inexpensive laptop seemed impossible until Mr Negroponte and the OLPC group placed a stake in the ground to build a $100 laptop—which in turn spurred the industry’s biggest players to create low-cost PCs. Mr Negroponte’s vision for a $100 laptop was not the right computer, only the right price. Like many pioneers, he laid a path for others to follow.

Intel Quits Effort to Get Computers to Children

SAN FRANCISCO — A frail partnership between Intel and the One Laptop Per Child educational computing group was undone last month in part by an Intel saleswoman: She tried to persuade a Peruvian official to drop the country’s commitment to buy a quarter-million of the organization’s laptops in favor of Intel PCs.

In Peru, where One Laptop has begun shipping the first 40,000 PCs of a 270,000 system order, Isabelle Lama, an Intel saleswoman, tried to persuade Peru’s vice minister of education, Oscar Becerra Tresierra, that the Intel Classmate PC was a better choice for his primary school students.

Unfortunately for Intel, the vice minister is a longtime acquaintance of Mr. Negroponte and Seymour Papert, a member of the One Laptop team and an M.I.T. professor who developed the Logo computer programming language. The education minister took notes on his contacts with the Intel saleswoman and sent them to One Laptop officials. WOOPS!

Intel drops out of One Laptop Per Child program

Intel said on Thursday it will drop out of the One Laptop Per Child project and resign from the board after the project’s board demanded the chipmaker stop supporting other efforts in emerging markets. (Reuters/Afolabi Sotunde)

2 Comments on "One Laptop Per Child (OLPC) – bad news & good news"

OLPC was back in the news last week with a report on the successful introduction of 50 of the ‘little green laptops’ to a hilltop Andean village, where primary school children got the machines six months ago:

“ARAHUAY, Peru: Doubts about whether poor, rural children really can benefit from quirky little computers evaporate as quickly as the morning dew in this hilltop Andean village … .These offspring of peasant families whose monthly earnings rarely exceed the cost of one of the US$188 (€130) laptops — people who can ill afford pencil and paper much less books — can’t get enough of their “XO” laptops. At breakfast, they’re already powering up the combination library/videocam/audio recorder/music maker/drawing kits. At night, they’re dozing off in front of them — if they’ve managed to keep older siblings from waylaying the coveted machines.”

Tiny, green and cute as a button

Mike Miner, Financial Post

… When it finally did arrive, the most common comment heard was “cute.” Second was “where can I get one?” (Since the [two-for-one]offer is over for now, there’s always eBay, where current bids are topping out at just under $800.) … Because of the competition from Intel and others, including India’s $120 NetPC, Mr. Negroponte had trouble drumming up the support to justify a large enough production run to create his ideal economy of scale on parts.

In the coming weeks, however, 100,000 of the tiny green computers will be shipped to Afghanistan, Cambodia, Ethiopia, Haiti, Mongolia and Rwanda.