Re Ian Bremmer 'Could third-party candidates upend the 2024 US election?' 3 April The current political movement in the USA…

Electoral College

Written by Diana Thebaud Nicholson // January 27, 2021 // Government & Governance, U.S. // Comments Off on Electoral College

The National Popular Vote bill would guarantee the Presidency to the candidate who receives the most popular votes in all 50 states and the District of Columbia.

Agreement Among the States to Elect the President by National Popular Vote

It has been enacted into law in 13 jurisdictions with 181 electoral votes (CA, CO, CT, DC, HI, IL, MA, MD, NJ, NY, RI, VT, WA). The bill will take effect when enacted by states with 89 more electoral votes. The bill is currently on the governor’s desk in Delaware and New Mexico. It has passed one house in 8 additional states with 72 electoral votes (AR, AZ, ME, MI, NC, NV, OK, OR), including a 40–16 vote in the Republican-controlled Arizona House and a 28–18 in Republican-controlled Oklahoma Senate, and been approved unanimously by committee votes in two additional Republican-controlled states with 26 electoral votes (GA, MO).

Majority of Americans continue to favor moving away from Electoral College

(Pew Research Center) Attitudes about the Electoral College remain deeply divided along partisan lines. Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents – especially liberal Democrats – say they would prefer changing the system to be based on the popular vote (71% of Democrats overall, including 82% of liberal Democrats, say this). Republicans and Republican leaners – especially conservative Republicans – prefer keeping the current system where the winner of the Electoral College takes office (61% of Republicans overall, including 71% of conservative Republicans, say this).

Overall, other demographic divides are relatively modest. Younger adults are somewhat more supportive of changing the system than older adults (60% of those ages 18 to 29 support changing the system, compared with 51% of those 65 or older). A similar divide emerges across levels of formal education. Those with postgraduate degrees are somewhat more supportive of changing the system than those with less formal education.

2020

11 December

The Electoral College meets Monday to vote. Here’s what to expect

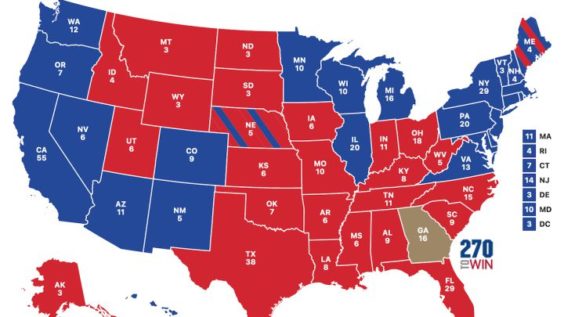

(PBS Newshour) The Constitution gives the electors the power to choose the president, and when all the votes are counted Monday, President-elect Joe Biden is expected to have 306 electoral votes, more than the 270 needed to elect a president, to 232 votes for President Donald Trump.

Who are the electors?

Presidential electors typically are elected officials, political hopefuls or longtime party loyalists.

This year, they include South Dakota Gov. Kristi Noem, a Trump elector who could be a 2024 Republican presidential candidate, and Georgia Democrat Stacey Abrams, her party’s 2018 nominee for governor and a key player in Biden’s win in the state. Among others are 93-year-old Paul “Pete” McCloskey, a Biden elector who is a former Republican congressman who challenged Richard Nixon for the 1972 GOP presidential nomination on a platform opposing the Vietnam War; Floridian Maximo Alvarez, an immigrant from Cuba who worried in his Republican convention speech that anarchy and communism would overrun Biden’s America, and Muhammad Abdurrahman, a Minnesotan who tried to cast his electoral vote for Sen. Bernie Sanders instead of Hillary Clinton in 2016.

9 December

How to get rid of the Electoral College

Elaine Kamarck and John Hudak

(Brookings) Next week five hundred and thirty-eight American citizens will travel to their state capitals and elect the president of the United States. These Americans, chosen for loyalty to their political party, will vote for the presidential candidate who won their state’s popular vote.[1] Only when they sign “the certificate of ascertainment” and the votes are tallied in the United States Congress is the presidential race officially over. As we all know only too well, in practice this archaic system means that the person who wins the most votes may not win the election.

13 November

Although Donald Trump refuses to concede, the 2020 Presidential Election has been called for Joe Biden, after the Associated Press on Saturday declared the Democratic challenger the winner in Pennsylvania, whose 20 electoral votes took him over the threshold of 270 needed for victory.

As of 17:00 ET on Friday, only Georgia was still to be called, with AP waiting until after a recount is conducted due to the narrow margin between Biden and Trump in the state.

8 November

Biden won the Electoral College. Now he should call for it to be abolished.

6 November

The Electoral College Is Close. The Popular Vote Isn’t.

The prolonged uncertainty in spite of the clear preference of the public has intensified some Americans’ anger at a system in which a minority of people can claim a majority of power.

With many ballots still left to count in heavily Democratic cities, former Vice President Joseph R. Biden Jr. was leading President Trump on Friday by more than 4.1 million votes. Amid all the anxiety over the counts in Pennsylvania and Georgia, and despite Americans’ intense ideological divisions, there was no question that — for the fourth presidential election in a row, and the seventh of the past eight — more people had chosen a Democrat than a Republican.

Only once in the past 30 years have more Americans voted for a Republican: in 2004, when President George W. Bush beat John Kerry by about three million votes. But three times, a Republican has been elected.

3 November

Bloomberg’s useful 2020 election lexicon

All the 2020 Vocabulary You Should Know for Election Day in America

From “naked ballots” to “safe-harbor deadlines,” here are the terms to know.

ELECTORAL COUNT: Electors meet in their states on Dec. 14 to cast their votes, and the incoming Congress will meet in a joint session on Jan. 6, 2021, to count them and declare the results. If either Trump or Biden have reached a majority of 270 electoral votes, they will be certified the winner in what is typically a pro forma affair. If not, then Congress would get involved in deciding the race.

SAFE-HARBOR DEADLINE: States have until Dec. 8 to resolve any disputes and certify their results and send a slate of electors to the Electoral College in order for them to be considered conclusive. In a worst-case scenario where a dispute lasts beyond that date, a state risks having its electors uncounted or having its dispute resolved by Congress.

No matter who wins, it’s time to get rid of the electoral college

Opinion by Katrina vanden Heuvel

(WaPo) Before today’s election, 9.7 million Texans had already voted — 108 percent of total ballots cast there in the last presidential election. In just four years, Texas has catapulted from second-to-last in voter turnout to a national leader in early voting. This is no coincidence. Now that this once-red state is emerging as a toss-up, residents are turning out in record numbers, believing that their votes will finally have a meaningful effect on the presidential election. Though this is a tremendous success story, it also underlines one of our Constitution’s greatest failures: Under the electoral college, some votes matter far more than others.

Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) may have said it best: “Call me old-fashioned, but I think the person who gets the most votes should win.” The electoral college is indeed an undemocratic travesty, and no matter who wins this election, it’s time for us to move toward a national popular vote.

21 October

What happens if Trump and Biden tie in the Electoral College?

(Brookings) In recent days stories in The Washington Post, the New York Times, and Politico, as well as statements by Biden campaign manager Jennifer O’Malley, all indicate that the presidential race is closer than people think. President Trump seems to have recovered from coronavirus and is back on the campaign trail, and polls in key states such as Florida and Pennsylvania seem to be tightening. An excellent piece by Tom Edsall in the New York Times amasses data showing that in some key states Republicans are registering to vote in numbers far greater than Democrats.

While none of these developments may be significant enough to overcome Biden’s large cash advantage and Trump’s bizarre and chaotic closing strategies, the possibility of a narrowing race that results in an Electoral College tie of 269 to 269 (my colleague Bill Galston’s “Nightmare Scenario”) is here.

The Constitution is pretty clear on how this plays out. If there is no winner in the Electoral College, Article 2, Section 1, Clause 3 states that the decision goes to the House of Representatives while the Senate picks the vice president. But the voting in the House is different from the Senate. In the vote for vice president, each Senator has one vote. But in the House each state has only one vote for president—regardless of its size—and a presidential candidate needs 26 states to win.

If the presidential race should end up in the House the outcome would depend on which party controls the state’s delegation. As it stands Republicans are in the majority, with control of 26 state delegations. Democrats control 23 state delegations and one state, Pennsylvania, has a tied delegation: 9 Democrats and 9 Republicans.[1] But the Congress is sworn in before the Electoral College votes are read out in the Senate. In the case of a tie it will be the next Congress not the current Congress that votes on the presidency, and a handful of 2020 congressional elections could decide the presidential election.

Can the Electoral College be subverted by “faithless electors”?

Russell Wheeler

American history has seen a handful of faithless electors—156 by one count—who vote for someone other than that candidate. Faithless electors have never changed an election outcome. But in this chaotic election year, their potential to disrupt the presidential election may loom larger. As a further twist, state legislatures in battleground states might try to replace state-certified electors with alternative slates of faithless-elector equivalents.

(Brookings) Every four years, Americans rediscover the 538-member Electoral College, the convoluted mechanism that the Constitution (Article II, section 1 and Amendment XII ), federal statutes, and state laws prescribe for selecting the president. Electors rarely appear on ballots, but when voters pull the lever for president and vice president, they are actually voting to authorize competing slates of electors who will cast the official votes at a later date.

The founders envisioned electors as free agents, selected by the voters to be what Alexander Hamilton described in Federalist 68 as “men most capable of analyzing” presidential candidates. Over the years most have forgotten that electors are actual people, and the Founders’ vision has morphed almost uniformly into 538 party-selected, faceless robots.

Following the November popular vote, each state formally designates its electors, specifically those electors selected by the political party of—and pledged to vote for—the state’s popular vote-winning candidate. In December those electors meet in each state to cast their official electoral votes, which the states send to Washington for January’s official tally. The winning side in all but Maine and Nebraska gets all the state’s electoral votes regardless of the popular vote division. The House of Representatives decides presidential elections if there is no Electoral College majority (most recently in 1824), although the 1876 election was resolved by horse trading after a special commission ended voting disputes.

Today’s electors pledge to vote faithfully for their party’s candidate. American history has seen a handful of faithless electors—156 by one count—who vote for someone other than that candidate. Faithless electors have never changed an election outcome. But in this chaotic election year, their potential to disrupt the presidential election may loom larger. As a further twist, state legislatures in battleground states might try to replace state-certified electors with alternative slates of faithless-elector equivalents.

13 September

The Case for Dumping the Electoral College

Trump’s Presidency, and the risk that it will recur despite his persistent unpopularity, reflects a deeper malignancy in our Constitution that must be addressed.

(New Yorker) …Trump may still win reëlection, since the Electoral College favors voters in small and rural states over those in large and urban ones.

… James Madison, who helped conceive the Electoral College at the Constitutional Convention, of 1787, later admitted that delegates had written the rules while impaired by “the hurrying influence produced by fatigue and impatience.” The system is so buggy that, between 1800 and 2016, according to Alexander Keyssar, a rigorous historian of the institution, members of Congress introduced more than eight hundred constitutional amendments to fix its technical problems or to abolish it altogether. In much of the postwar era, strong majorities of Americans have favored dumping the College and adopting a direct national election for President. After Kefauver’s hearings, during the civil-rights era, this idea gained momentum until, in 1969, the House of Representatives passed a constitutional amendment to establish a national popular vote for the White House. President Richard Nixon called it “a thoroughly acceptable reform,” but a filibuster backed by segregationist Southerners in the Senate killed it.

… Today, it effectively dilutes the votes of African-Americans, Latinos, and Asian-Americans, because they live disproportionately in populous states, which have less power in the College per capita. This year, heavily white Wyoming will cast three electoral votes, or about one per every hundred and ninety thousand residents; diverse California will cast fifty-five votes, or one per seven hundred and fifteen thousand people.

10 September

Electoral College Rating Changes: Florida and Nevada Shift Right

(Cook Political Report) Today we are making two ratings changes in Pres. Trump’s favor, moving Florida from Lean Democrat to Toss Up, and Nevada from Likely Democrat to Lean Democrat.

Biden’s Electoral College lead has narrowed to 279 to 187 for Trump. Earlier this summer, Biden held a 308 to 187 lead.

12 August

The Democratic Popular Vote Lock

By Ed Kilgore

Since Trump’s strategy assumes another Electoral College win combined with a popular vote loss, a record- a record-breaking Democratic streak is, well, nearly a lock. And unless the Republican Party gets serious about expanding its narrow coalition to include nonwhite voters and urban areas, its presidential candidates will likely to continue to rely on an Electoral College advantage to win the presidency – until they lose and are forced to change.

But unfortunately, they have another, sinister option: hanging onto power by strengthening the institutions – not just the electoral college, but the U.S. Senate, the states, the federal courts – that allow for minority rule. And they can also continue to thwart popular majorities by building rather than filling potholes on the path to the ballot box.

… As for Democrats, they can continue to agitate for a constitutional amendment abolishing the Electoral College or some scheme to neutralize it (e.g. the National Popular Vote Initiative, an interstate compact whereby states pledge to cast their electoral voters for the national popular vote winner); the former would take many years and the latter could be challenged in court as unconstitutional. The surest route to protection of minority rights is probably via voting rights activism, assuming Democrats win both Congress and the White House this year

3 August

How Has the Electoral College Survived for This Long?

Resistance to eliminating it has long been connected to the idea of white supremacy.

By professor of history and social policy at Harvard and the author of “Why Do We Still Have the Electoral College?”

(NYT Opinion) The notorious formula that gave states representation in Congress for three-fifths of their slaves was carried over into the allocation of electoral votes; the number of electoral votes granted to each state was (and remains) equivalent to that state’s representation in both branches of Congress. This constitutional design gave white Southerners disproportionate influence in the choice of presidents, an edge that could and did affect the outcome of elections.

…the white supremacist regimes of the South stood as a roadblock in the path of a national popular vote from the latter decades of the 19th century into the 1960s, when the Voting Rights Act and other measures compelled the region to enfranchise African-Americans. There was, of course, resistance to the idea of a national vote elsewhere in the country, but it was the South’s well-known adamance — and the fact that Southern states alone could come close to blocking a constitutional amendment in Congress — that kept the idea on the outskirts of public debate for decades.

… The politics of race and region also figured prominently in the stinging defeat of a national popular vote amendment in the Senate in 1970 — the closest that the United States has come to transforming its presidential election system since 1821. Popular and elite support for the idea had mushroomed in the 1960s, leading in 1969 to the House of Representatives voting overwhelmingly in favor of a constitutional amendment that would have abolished the Electoral College. The proposal then got bogged down in the Senate during a year when regional tensions were high: two Southern nominees to the Supreme Court were rejected by the Senate, and the Voting Rights Act was renewed over the vocal opposition of Southern senators. Meanwhile, the national popular vote amendment was stalled in the Judiciary Committee, which was chaired by none other than [the Mississippi segregationist] Senator Eastland.

… Southern political leaders, shaped by segregation and white supremacist beliefs, thus kept the idea of a national popular vote off the table for many decades and played a crucial role in blocking its passage through Congress at a historical juncture when change actually seemed possible. To be sure, electoral reform is almost always a complex, difficult process, with diverse actors competing to defend their ideas and interests. But had the politics of race been less salient, both in the 19th century and the 20th, the Electoral College would most likely have been relegated long ago to the status of a historical curiosity. We might want to keep that sobering fact in mind as we look ahead to an election whose outcome is in question only because of the peculiar manner in which we choose our presidents.

6 July

Can We Please Pick the President by Popular Vote Now?

The Supreme Court’s unanimous decision in the “faithless electors” case is another reminder of how antiquated and undemocratic the Electoral College is.

The Supreme Court clearly got it right on Monday when it ruled that the Electoral College can keep working the way it has worked for the last 200 years.

The justices did not address the much bigger problem, which is the existence of the Electoral College itself.

In a unanimous opinion written by Justice Elena Kagan, the court agreed that states may replace and even punish “faithless electors,” the curious term we use for the direct electors of the president who cast their ballots for a candidate other than their party’s nominee.

According to the Constitution’s plain language, each state appoints its electors “in such manner as the legislature thereof may direct.” That power, Justice Kagan wrote, “includes power to condition his appointment — that is, to say what the elector must do for the appointment to take effect.”

13 March

Trump Can’t Cancel the Election. But States Could Do It for Him.

(Slate) There’s a perfectly legal shortcut around a free and fair presidential election.

The president can ask Republican-controlled state legislatures to assign their electoral votes to him—without allowing any citizen to cast a ballot for president. This maneuver would constitute an appalling assault on democracy. But it would be legal.

…There are 538 electors, and a candidate needs 270 of them to win. Currently, every state assigns electors to the candidate who won the popular vote statewide. But the Constitution does not require states to assign their electors on the basis of the statewide vote. … Rather, it explains that each state “shall appoint” its electors “in such manner as the Legislature thereof may direct.” In other words, each state legislature gets to decide how electors are appointed—and, by extension, who gets their votes.

In the first presidential election, for instance, the legislatures of Connecticut, Delaware, Georgia, New Jersey, and South Carolina appointed electors directly. Eventually, every state moved toward the modern system. But the Supreme Court confirmed in 1892’s McPherson v. Blacker that states were free to revert to the old method, and in 2000’s Bush v. Gore, the court reiterated this point. The majority declared that the state legislature “may, if it so chooses, select the electors itself,” and retains authority to “take back the power to appoint electors” even after switching to a statewide vote.

Put simply, it is perfectly constitutional for a state legislature to scrap statewide elections for president and appoint electors itself. It would also be constitutional for a state legislature to disregard the winner of the statewide vote and assign electors to the loser. And because the Constitution grants legislatures the authority to pick electors this way, Congress cannot stop them.

Due in part to partisan gerrymandering, Republicans control the legislatures of 28 states. Collectively, these states have 294 electoral votes. Trump himself could not cancel the entire presidential election. But he could ask these GOP-dominated legislatures to cancel their statewide presidential elections and assign their electors to him. It’s doubtful that we will face this situation in November. But imagine a worst-case scenario…

2019

22 March

The Electoral College’s Real Problem: It’s Biased Toward the Big Battlegrounds

A winner-take-all system within states can produce results counter to the majority for no high-minded reason.

(NYT) There are legitimate arguments to keep the present winner-take-all system, even arguments that today’s progressive opponents of the Electoral College could appreciate. In the 1880s, for instance, it limited the electoral gains that white supremacist Democrats reaped by disenfranchising black voters.

But the Electoral College also brings the risk of anti-majority outcomes — in which the winner of the national popular vote loses the election — for no high-minded reasons at all, as occurred in 2000 and 2016. It even has the potential to worsen the kind of crises it was intended to prevent.

States are awarded electoral votes based on the number of representatives in the United States House, which is essentially proportionate to a state’s population, and on the number of senators, which is not. So California gets two electoral votes from its two senators, and much smaller Wyoming also gets two votes from its two senators. Over all, 81 percent of electors are awarded by population, and 19 percent are awarded equally among the states and the District of Columbia.

There are circumstances in which this modest bias can prove decisive: a near Electoral College tie, as in 2000. After falling short in Florida, Al Gore lost to George W. Bush by five electoral votes, less than the net 18 votes Mr. Bush gained from small-state bias. But for perspective, that’s the only Electoral College outcome since 1876 that was within the 20 or so electoral-vote margin for the small-state bias to matter.

The Electoral College’s small-state bias had essentially nothing to do with Donald J. Trump’s victory. In fact, he won seven of the 10 largest states, and Hillary Clinton won seven of the 12 smallest states.

The true quirkiness of the Electoral College comes from how states award their votes, not how many votes each state has: It’s (largely) winner-take-all.

This is the feature that defines the character of American presidential elections. A candidate who narrowly wins the tipping-point states will win the presidency, regardless of the margin of victory in the rest of the country. That means there’s no incentive for candidates to campaign in any noncompetitive state, whether it’s a populous one like California or the opposite, like North Dakota.

It’s Time to Kill the Electoral College, One of America’s Original Sins

Beating the rigged math, as Obama did, produced a backlash so strong that we sent Trump to the White House. We deserve better.

(Daily Beast) When calculating legislative representation and taxation, the 1787 Constitutional Convention decided only three out of every five slaves would count as a person. In what became known as the three-fifths compromise, Southern states were allowed to count their slaves at a discount and walked away with half as many more seats. That meant an increase from 33 congressional seats to 47, and a similar advantage in Electoral College votes.

According to History Central, the Electoral College was “created for two reasons.” First was creating a “buffer between population and the selection of a President,” meaning its 538 voting members could effectively override the popular vote if need be. Some believed that citizens located far from the nation’s capital would not truly understand the issues and would be less familiar with the candidates. For context, this was decades before the Pony Express was formed and centuries before the first Twitter feud broke out. In other words, there were people quite literally closer to the center of power who were better informed to make those choices for everyone else.

Secondly, there is the claim that direct election of presidents was shelved to balance the interests of the states. Thus, smaller less populous states received additional power—with their votes worth more than those of larger states thanks to the two additional electoral votes for each senator—out of a bastardized sense of egalitarianism. At the time, those states with the smallest populations tended to be more rural and in the South. The Electoral College was negotiated to protect them and their way of life.

…on its face, leaving the presidency in the hands of 538 elites, rather than directly beholden to the American people, is antithetical to everything conservatives say they believe. But, without it—without gerrymandering, targeted voter suppression and laws supposedly designed to equalize power among the states rather than allowing those decisions to rest with the citizenry—in all likelihood, conservatism would have a tough time maintaining its national political footing. They—and everyone else—would be forced onto an equal playing field.

21 March

(WaPo) Liberals have been ramping up their criticism of the electoral college, and most Republicans have been ramping up their defense. Marc Thiessen, for example, says the Democrats are “pursuing a tyranny of the majority.”

But conservative columnist Henry Olsen says conservatives should abandon this antidemocratic system before it’s too late. He proposes an intriguing compromise:

If the Constitution is to be amended to elect the president via a popular vote, conservatives should develop national voter legislation so that all people in all states have the same rights and opportunities. This means conservatives should include as part of the constitutional amendment a voting process that meets liberal desires for things such as automatic enrollment and early voting joined with conservative desires for ballot integrity, voter-ID mandates and requiring each voter registration to list a valid Social Security number. This would be a classic compromise in that each side would get something it valued highly.

Getting Rid of the Electoral College Isn’t Just About Trump

But does anyone really think popular vote losers make better presidents?

By Jamelle Bouie

(NYT) …on Monday night, Senator Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts called for shutting down the Electoral College. “I believe we need a constitutional amendment that protects the right to vote for every American citizen and to make sure that vote gets counted.”

It’s not hard to guess why Republicans are riled by Warren’s embrace of a national popular vote. Without the Electoral College, neither Trump nor his Republican predecessor George W. Bush would have won the White House on their first go-round. At the same time, these self-interested or party-specific arguments are part of a larger conversation.

28 February

The Electoral College Is the Greatest Threat to Our Democracy

The Electoral College routinely threatens or produces perverse outcomes, where the will of the voters is thwarted by an ill-considered 18th-century electoral device.

By Jamelle Bouie

(NYT) It’s still well under the radar, but the movement to circumvent the Electoral College gained ground this week. On Sunday, Jared Polis, the governor of Colorado, said he would sign a bill to join the National Popular Vote interstate compact, whose members have pledged to give their electoral votes to the winner of the national popular vote. The Maine Legislature, likewise, is mulling membership and will hold hearings to discuss the issue. … If direct election of the president would give equal weight to all votes, then the Electoral College works to give outsize weight to a narrow group of voters in a handful of states. That bias is why Donald Trump is president. A healthy plurality chose his opponent, but his supporters dominated key “swing” states.

It could happen again. A 2018 report on America’s future political demography found four realistic scenarios in which Democrats win the national popular vote but lose the Electoral College because of the geography of the electorate. The 2020 election could be the third time in six elections that the White House went to the loser of the popular vote.

… The presidency went to the popular-vote loser in 1824 (John Quincy Adams; his opponent, Andrew Jackson, also won the most electoral votes), 1876 and 1888. In the 20th century, Americans had close calls in the elections of 1948, 1960, 1968 and 1976, with near splits in the popular and electoral vote. Despite winning the popular vote in six of the past seven presidential elections, Democrats have held the presidency for only four of those terms, under Bill Clinton and Barack Obama.