2019

1 October

China at 70: Beijing projects power. But this has its limits

China’s military capability is impressive. But Hong Kong shows this isn’t enough. There are lessons for India

By C. Uday Bhaskar

(Hindustan Times) Military parades are an indicator of the strategic culture of a nation and India has its own version in the January 26 celebrations. Without in any way suggesting that Delhi ought to emulate Beijing, some elements of the October 1 parade warrant comparison with the Indian experience. China’s visible success in indigenous defence design and production has eluded India, and Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s current focus on “Make in India” is still a work, alas, in wobbly progress.

In contrast to the single-minded political determination in China to create a cost-effective and time-cognisant indigenous industrial ecosystem that could nurture a military production base, the Indian experience has been bleak. Political interest in matters related to military is episodic, and the more recent penchant to make exaggerated claims of military prowess, which is notional, is a case of India “carrying a weak stick but speaking loudly”.

The embarrassing Hong Kong episode that sullied the image of grand splendour and self-assurance that China at 70 wanted to exude pointed to the limits of efficacy of military power in internal security. As the Modi government grapples with the post August 5 Kashmir imbroglio, the subtext of the October 1 parade may be instructive.

6 June

C. Uday Bhaskar: Wary of China, India draws closer to the US – just not too close, as the loss of its special trade status shows

(SCMP) The punitive trade move comes even as the US publicly embraces India as a key partner in its Indo-Pacific strategy against China. The contradictory moves are part of a long and uneasy alliance between the two countries

The trade decision to penalise India is at odds with America’s Indo-Pacific strategy, a report of which was recently unveiled at the Shangri-La Dialogue in Singapore, and which lists India among the major partners of the US in this collective endeavour.

The report, titled “Preparedness, Partnerships, and Promoting a Networked Region”, is the distillate of the Trump security vision for the Indo-Pacific region, and notes that the US and India maintain a “broad-based strategic partnership” and asserts that this has “strengthened significantly during the past two decades, based on a convergence of strategic interests”.

The report states the primary concern for US national security as: “Inter-state strategic competition, defined by geopolitical rivalry between free and repressive world order visions”. China is identified as the revisionist power determined “to reorder the region to its advantage by leveraging military modernisation, influence operations, and predatory economics to coerce other nations”.

2018

1 May

Minhaz Merchant: Why Modi and Xi Jinping are new grandmasters of the geopolitical chess game

Afghanistan is where the winning moves will be made.

(DailyO) Xi wants India to join the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), though China’s vice-foreign minister Kong Xuanyou said in Wuhan, “China won’t force it on India to or be too hard on it.”

Without India’s participation, however, the BRI will lack legitimacy. Kong’s statement is, therefore, more pragmatic than definitive.

Enter Afghanistan. Xi knows that the United States is already encouraging India to play a larger economic role in Afghanistan. The decision by Xi and Modi to work jointly on economic projects in Afghanistan satisfies three Chinese concerns and two Indian ones.

First, India-China infrastructure projects will indirectly draw India into the BRI which, as Xi announced late last year, will extend to Afghanistan.

Second, for that to happen, peace must return to Afghanistan with the Pakistan-sponsored Taliban joining an Afghan coalition government at some stage. The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), part of the BRI, already faces security threats from Baloch insurgents. Restoring peace in the region is therefore key to BRI’s success. India’s economic role in Afghanistan, now backed by China, can help. …

As a shrewd strategist, Modi sees two benefits from Xi’s gameplan. The first is neutralising Pakistan. While Xi has his own geostrategic reasons for drawing India into a pan-Asian orbit, Modi knows that joint India-China economic projects in Afghanistan will cool Pakistan’s fevered opposition to India’s growing role in a country Islamabad has long coveted as part of its strategic depth theory.

The second benefit for India in Xi’s new overtures is that a joint India-China co-operation lowers the temperature on the eastern front. With India’s military still under-equipped to fight a two-front war, a modus vivendi with Beijing will help the Indian Army focus on counter-terrorism operations in Jammu & Kashmir and infiltration of terrorists across the Line of Control (LoC).

6 March

Indian Navy’s MILAN ‘18: Towards Steadier Waters in Indo-Pacific

By C. Uday Bhaskar

(The Quint) India is hosting its week-long biennial naval engagement, MILAN 2018, in Port Blair on Tuesday, 6 March, and 16 navies from across the Indo-Pacific oceanic continuum will be a part of this demonstration of maritime camaraderie

Regional geo-politics cannot be divorced from such events and given the sequence of developments related to the Maldives over the last few months, the island nation has conveyed its inability to join ‘MILAN 2018’. However, the other nations include Australia, Malaysia, Mauritius, Myanmar, New Zealand, Oman, Vietnam, Thailand, Tanzania, Sri Lanka, Singapore, Bangladesh, Indonesia, Kenya and Cambodia.

China’s Increasing Footprint

The maritime domain, with specific reference to the extended Indo-Pacific, is now the focus of a latent contest and competition between China and the US-led regional alliance, that includes Japan, South Korea, Australia and an uneasy ASEAN.

It is against this backdrop that ‘MILAN’ acquires a certain specificity, where the symbolism is inversely proportional to the substantive content of the 16 navies meeting under one umbrella. As former prime minister Manmohan Singh had once noted in a pithy manner – the world wants India to emerge and grow strong. The contrast with the anxiety triggered by the rise of an assertive China is palpable across South East Asia.

26 February

Prepare for a Tougher China as Xi Sets in For the Long Haul

By C. Uday Bhaskar

(The Quint) With President Xi now firmly set for a third and perhaps fourth term, India will have to prepare for a Beijing that will be more assertive – whether it is the South China Sea dispute or Doklam standoff. The texture of the India-China bi-lateral relationship – whether it will be more brittle and discordant, or malleable and accommodating, will be determined by the perspicacity and integrity, or the lack thereof that President Xi will bring to his office — with the new-found assurance that there is no term limit to mark an end to the ‘Xi era’ in Chinese politics.

12 February

Panos Mourdoukoutas: China Wants To Turn The Indian Ocean Into The China Ocean

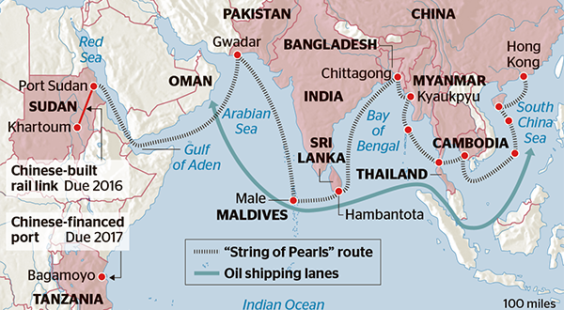

(Forbes) To execute this grand plan, Beijing is investing heavily in several infrastructure projects. Like Sri Lanka’s ports of Colombo and Hambantota, which give Beijing a trade outpost into the Indian Ocean. And the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), a colossal infrastructure project, which connects China’s western territories to the Indian Ocean.

But that’s the old news. The new news is that China is turning Maldives into another trading outpost with the acquisition of land there, and the signing of a free trade agreement.

These developments have irked India, for a couple of reasons. One of them is economic. Sri Lanka and Maldives can serve as a base for China to flood the Indian market with its products. Malvides, for instance, has a free trade agreement with both India and China. This means that Beijing can send products to Maldives first, and then re-export them to India.

The other reason is geopolitical. China wants to encircle India by turning trade outposts into military outposts.

5 February

India-China Tensions Flare Vying for Indian Ocean Region Control

India’s maritime policy has been constructive in the recent past where policymakers are concerned about China’ assertive policy towards the country as well as its growing influence in the Indian Ocean that they view as an attempt to gain permanent access to the waters and ‘encircle’ India strategically.

(The Quint) The competition between India and China is heating up in the Indian Ocean region with the regional powers’ moves to exert influence in the domain through development of port facilities and military patrols.

According to a recent US report, China is constructing a second military base in Jiwani, south west of Gwadar, that could be seen as part of its ‘String of Pearl strategy’ to expand its presence in the region.

This is effectively counterpoised by the recently inked pact signed between India and Seychelles which allows India to develop, manage, operate and maintain facilities on the Assumption island as part of its quest to boost influence in the Indo-Pacific strategy.

Historically India has viewed the Indian Ocean as its ‘backyard’ which first manifested during the Cold War period where it wanted the major powers to withdraw themselves from the region as it constituted a threat to India’s presence in the region.

However, China’s increasing reliance on energy security and its trade with the Indian Ocean littorals act as determinants to its increasing strategic calculus in the region. Compounded with the economic imperatives, China’s motive to utilise the Indian Ocean as the space for its power projection capabilities has complicated the regional stability.

See also: China’s Indian Ocean Strategy

2017

18 September

Explained: India-China Standoff at the Border

28 August

Doklam faceoff ends: A new benchmark for the India-China bilateral?

By C. Uday Bhaskar

The statement of the Indian foreign ministry on Monday (August 28) indicating that Delhi and Beijing have agreed to “expeditious disengagement” of their border personnel at the Doklam face-off in Bhutan is both significant and welcome.

This is a return to the status quo that existed prior to June 16 – and it may be recalled that Bhutan’s initial objection was to the manner in which China was building a road towards the Doklam plateau that had triggered the face-off.

The timing of this modus vivendi that has allowed both sides to claim a satisfactory outcome can be linked to the forthcoming BRICS summit to be hosted by China. President Xi Jinping would have had a fractured summit if the Indian Prime Minister had chosen not to attend – and hence the urgency to resolve Doklam.

The Modi team exuded commendable restraint and firmness in dealing with Doklam – from the time it came into the public domain in mid June, and this was in contrast to the rather shrill turn of phrase and sentiment expressed by Beijing that sought to intimidate Delhi.

The Doklam resolution will represent a new benchmark for the India-China relationship and will also be closely studied by the extended Asian neighbourhood – as also the major powers – to appropriately comprehend the sub-text of how Delhi was able to satisfactorily deal with an unacceptable degree of assertiveness that Beijing was seeking to exude.

21 August

India vs China: Clash of the titans

A border dispute high in the Himalayas puts the decades long “cold peace” between India and China under severe strain.

By Richard Javad Heydarian

(Al Jazeera) The decades-long “cold peace” between India and China is actually under severe strain. For the last two months, hundreds of Indian and Chinese soldiers have been squaring off over a “tri-juncture”, which tenuously separates India, Bhutan and China thousands of kilometres above sea level.

There have reportedly been clashes between the two sides, with Chinese and Indian soldiers throwing stones at each other, but so far stopping just short of firing their guns. But tensions are rising every day, with diplomatic patience wearing thin. The two Asian giants, collectively home to a third of humanity, are once again on the verge of direct military conflict with frightening implications for the region and beyond.

At the heart of the new round of tensions is the Doklam plateau, which lies at a junction between China, the northeastern Indian state of Sikkim and Bhutan, is currently disputed between Beijing and Thimphu. India supports Bhutan’s claim. India and China already fought a war over the border in 1962, and disputes remain unresolved in several areas.

Throughout the decades, continental-size China, with 14 land neighbours and six sea neighbours, has been embroiled in 23 border disputes. Many have been resolved, particularly with Russia and central Asian republics, but those with the likes of India, Vietnam and Japan have festered in recent years.

13 August

Cleo Paskal: World is watching the Doklam stand-off

(Sunday Guardian) While much of the Western media is blaring North Korea, many key commentators and analysts are closely tracking the situation in Doklam. They have realised that, embedded in the stand-off, are many of today’s key strategic questions.

Will China’s expansion continue unchecked? Will India become a net security provider not only for itself, but for its allies? Will China put an aggressive PLA agenda above domestic economic growth? And more.

The answers resonate far beyond Doklam, and are being examined in capitals around the world.

In terms of China’s expansion, Western media largely sees the Doklam road in the context of Beijing’s other status quo disturbing infrastructure projects, such as the militarising of islands and reefs in the South China Sea. CNN’s recent article on the situation highlights that China’s moves “come amid increasing Chinese military activity throughout Asia”.

The road also casts a new light on the “benignness” of the One Belt One Road initiative. While some commentators reference China’s attempts to make historical claims in Doklam, most also imply that there is no economic or social reason for the road. It only makes sense in the context of weakening Bhutan and threatening India.

Another key question raised by Doklam, and being increasingly discussed in the West, is what is the relationship between China and Pakistan (and/or Pakistan-based terrorist organisations)? The Daily Mail ran a feature about Lashkar-e-Taiba’s Amir Hamza releasing a video in which he says, “If India will send its army in Bhutan to counter China, then along with Pakistan, Chinese troops will enter Srinagar.” The Daily Mail noted, “This video is the first such proof of Lashkar-e-Taiba’s direct involvement in the Northeast and their strategy to work along with China.”

This combined with the widely reported quote from Long Xingchun, director of the Center for Indian Studies at China West Normal University that “under India’s logic, if the Pakistani government requests, a third country’s army can enter the area disputed by India and Pakistan, including India-controlled Kashmir”. Especially taken together, the two approaches make it clear that, at the very least, elements within Pakistan and China consider themselves aligned against India.

12 August

Doklam Standoff Explained: Who’s Involved & Why’s India Bothered?

(The Quint) Since June this year, Indian and Chinese troops have been locked in a face-off at the border trijunction with Bhutan. Trijunction matlab? Where the borders of China, India and Bhutan meet. Now, the area in question is called the Doklam plateau – 89 sq kilometres that China claims as its own (no surprises there!)

Rewind to 16 June, when India went into Doklam and told the Chinese People’s Liberation Army to give it a rest – aage raasta bandh hai! But India also quickly added, “not for me bro, for Bhutan… I’m intervening on behalf of Bhutan.”

If you look at the map, Doklam lies very close to Chumbi Valley, a tiny slice of Tibetan territory that overlooks India’s ‘Chicken Neck’ – the Siliguri corridor – which is India’s only narrow link to its northeast. So if India allows China to claim Doklam, we’ll basically be handing the PLA a readymade launchpad to cut off the northeastern states.

Besides, China has already built a highway that allows the 500 kilometre journey from Lhasa up to Chumbi Valley to be completed in just eight hours. Not only this, in the next two years, the Beijing-Lhasa railroad will allow Chinese troops to march right up to India’s entrance, the Nathu La pass.

9 August

After 50-Day Doklam Standoff, China’s Defense Ministry Invites Indian Media Over

China’s Defense Ministry tries to send a goodwill signal directly to India.

(The Diplomat) China and India have been locked in a standoff in the Doklam area for 50 days after Indian troops stopped the Chinese Army from building a road in the area in mid-June. To break the ice, China’s Defense Ministry invited a delegation of Indian media over to the ministry for a direct dialogue on August 7. However, the meeting was not made public by the ministry on its website nor reported by Chinese local media until now.

According to multiple Indian media outlets, a few Indian journalists have been visiting China’s Defense Ministry in Beijing and having face-to-face dialogues with high-level officers of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA). The dialogue was organized by the All China Journalist Association, a semi-governmental organization led by the Communist Party of China.

Although [China’s Defense Ministry’s spokesman, Sr. Col. Ren Guoqiang] reaffirmed China’s position that “Indian troops must withdraw from the Doklam spot and no one should not underestimate China’s resolve to defend its territory,” he also emphasized several important details to show that China didn’t mean to provoke India in the first place.

Ren pointed out that “out of goodwill” China had informed India twice — on May 18 and againJune 8 — about China’s plan to build the road in the area, through the border meeting mechanism. However, India never replied to China until the standoff broke out.

11 July

In the Tri-Junction Entanglement, What Does Bhutan Want?

(The Wire) In the Doklam plateau in the west, the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) is known to have made frequent intrusions since the mid-1960s. Talks with China began in 1972, but since 1984, negotiations became bilateral without India’s participation. The two countries managed to sign an Agreement on Maintenance of Peace and Tranquillity in the Bhutan-China Border Areas in 1998. Thus far, 24 rounds of discussion have taken place under the agreement. The last round was held in August 2016 in Beijing between Chinese vice foreign minister Liu Zhenmin and Bhutanese foreign minister Lyonpo Damcho Dorji. However, the Chinese have recently claimed that Bhutan and China have a basic consensus on the functional conditions and demarcation of their border region.

At the heart of the issue is the lingering suspicion in India about the possibility of Bhutan ceding the Doklam plateau – located on the strategic tri-junction of Bhutan, the Chumbi Valley in China and the state of Sikkim in India. The area is extremely critical to India’s security as it overlooks the Siliguri corridor. China, on the other hand, has held a tough position on Doklam and has been upgrading infrastructure networks, including roads in nearby areas, on the lines that it has built in Aksai Chin.

9 July

Doklam Standoff: China Violates Agreements With India And Bhutan – Analysis

(Eurasia Review) On June 16, a Chinese PLA construction party entered Doklam area and attempted to construct a road. Doklam, on the edge of Chumbi valley and adjacent to the India-China-Bhutan tri junction is emphatically Bhutanese territory which China has been claiming with military muscle power and propaganda against the tiny and weak Himalayan Kingdom for decades now. The Chinese foreign ministry and official media have stated that Doklam is “indisputably” Chinese sovereign territory.

A Bhutanese army patrol tried to dissuade the PLA from construction telling them to withdraw to the pre-June 16 position. The Bhutanese government through its embassy in New Delhi issued a protest on June 20 to the Delhi Embassy in New Delhi. (The two countries do not have diplomatic representation in each other’s countries and work through their embassies in New Delhi).

2016

25 October

Use Of Water As A Strategic Weapon – Analysis

(Eurasia Review) While the border dispute between India and China remains unresolved, and political differences widen on bilateral as well as regional issues, water has emerged as yet another issue where differences are widening with the potential of conflict in the future. India is worried about China’s dam projects on the Brahmaputra river and both countries are asserting to defend their national interests and claims in controlling the water as it flows from the Tibetan plateau to the riparian states downstream in India and Bangladesh before joining the Bay of Bengal.

No sooner than China successfully blocked India’s entry into the Nuclear Suppliers Group and equating India with Pakistan’s claim for the same, India announced plans to assert its rights within the Indus Water Treaty with Pakistan. China retaliated within days of India’s announcement saying that it was building a dam on a tributary of the Brahmaputra (known as Yarlung Zangbo (Tsangpo) in Tibet). It soon transpired that China’s announcement on 1 October of the blockade of Xiabuqu river in Tibet is part of the construction of its “most expensive hydel project”. As a lower riparian state, India will be directly affected.

… India fears that if China builds dam projects in the Tibetan plateau, it would threaten to reduce flow of river water into India. Water is a critical resource for any nation that fetches rich economic dividend and therefore a country can use water by constructing dams, canals and irrigation systems as political weapon, which can be used both in war and also during peace time.

28 August

Gordon Chang: India’s Grand Gamble With China

India and China are now confronting each other across the board, and their disputes are only bound to get worse. “Modi has accomplished a lot, and India remains a mostly positive story,” [Eurasia Group’s Ian] Bremmer writes. “But the pace of progress is about to slow, and ghosts from the past are now circling overhead.”

For India, the biggest ghost is China. Modi looks like he wants to fundamental[ly] reorder relations with Beijing with a grand gamble. Should he succeed, the prime minister will know his country will be far more prosperous and secure.

(Forbes) India is also the world’s fastest-growing major economy, even if the numbers reported by the Central Statistics Office are too high, and it will roll into the G20 meeting next week with a lot to brag about.

Bremmer however, raises an issue that Modi may not be able to handle, something that troubles many, both inside and outside India. Reform, he predicts, will stall in two major areas, labor rules and land rights.

And the well-known analyst suggests democracy is partly responsible. There are more than a dozen state elections next year and in 2018. Then, there’s the nation-wide poll in 2019. “To protect his party’s vote share, Modi is seeking populist causes,” Bremmer writes. “Unfortunately, this strategy has begun with a much tougher attitude toward Pakistan.”

Everyone agrees that increased friction between India and Pakistan would be unfortunate, but there is an air of inevitability about it. New Delhi is coming to the realization that it has to do something about its hostile neighbor. “Terrorism is a clear and present danger in India, and many of the most serious attacks have links to Pakistan, including the 2001 attack on the Indian Parliament, the 2008 Mumbai attacks, the 2011 Mumbai bombings, and the attack this January on the Indian air base at Pathankot,” Cleo Paskal, a Trudeau Visiting Fellow at the Montreal Centre for International Studies, told me late last week. … “If the Pakistani military wanted peace with India, there would be peace with India,” she said to me. “And Pakistan’s military has the strong backing of China, in part because it suits Beijing to destabilize India.”

India claims Gilgit, which Pakistan controls, as well as the part of Kashmir under administration of Islamabad. In Balochistan, a long-simmering insurgency threatens China’s cherished project, the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor.

The Corridor connects China’s so-called Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region with the Indian Ocean through north-south roads bisecting Pakistan. Those road cross Balochistan. The strategic Gwadar port is in that province, which includes more than 40% of the area of Pakistan.

The unhappy Uighurs in the north, in Xinjiang, and the rebellious Balochs in the south threaten ground traffic through Beijing’s project. Modi, some believe, hit back at China in his speech by giving encouragement to the long-repressed Balochs.

26 June

NSG row: India-China rift out in open

During the plenary meeting of the 48-member NSG in Seoul, China blocked meaningful discussion on India’s participation

By C Uday Bhaskar

(Business Standard) The plenary meeting of the 48-member NSG (Nuclear Suppliers Group) in Seoul ended on June 24 with no specific reference to India’s application as a participating government. China supported by a few other nations was able to block any meaningful discussion on the subject – much to India’s disappointment.

This inconclusive result, for sure, is a tactical setback for Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government but not quite the disaster that some voices in the political spectrum have made it out to be. However, the fallout of Seoul can have long-term implications for the India-China bilateral relationship and the related realization of the ‘Asian century’.

Apropos Seoul, the first question that needs to be addressed objectively is whether formal admission to the NSG as a participating government is a desirable objective for India to pursue. The context is that Delhi was accorded an exceptional waiver in late 2008 by the same group – the NSG which enabled it to engage in nuclear commerce. The short answer is yes – the objective is desirable. The non-linear benefits of such status are not insignificant.

19 June

India needs to recaliberate NSG stance ahead of Seoul meeting

By C Uday Bhaskar

China is unlikely to alter its current orientation about the South Asian nuclear framework – which is to keep India in extended disequilibrium. In the face of such cynical realpolitik, New Delhi will have to review its own approach to the NSG and the political capital it wishes to expend in the run-up to Seoul.

(Business Standard) China has just tipped its hand in relation to India ahead of the Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG) plenary in Seoul on June 24.

An op-ed in the Global Times (June 14) titled ‘India mustn’t let nuclear ambitions blind itself’ gravely noted: “Beijing insists that a prerequisite of New Delhi’s entry is that must be a signatory to the Non-Proliferation Treaty, (NPT) while India is not. Despite acknowledging this legal and systematic requirement, the Indian media called China’s stance obstructionist.” This brief comment is the first semi-official articulation of China on the NSG and predictably obfuscates the issue.

In making this assertion about the NPT, Beijing is being characteristically innovative and artful in how it first distorts and then presents various facts specific to the nuclear domain.

17 April

Clearing Cobwebs: Will Parrikar’s China Visit Allay India’s Fears?

C Uday Bhaskar

— India and China share a very complex and contradictory relationship that has many aspects to it.

— Border stability at the tactical level has been internalized reasonably satisfactorily by the Modi-Xi combine.

— An anxious India suspects that China is determined to keep India in a state of extended disequilibrium.

— China has tacitly endorsed the Pakistani build-up of fissile material and nuclear weapons.

— The much heralded Asian century cannot be a reality unless both nations realise their enormous domestic economic potential.

2015

7 September

China’s economic slowdown – India’s opportunity?

China’s recent downturn has led to a reassessment of global economic growth, with analysts pointing to how India may benefit from the slowdown. But is the South Asian nation set to become the world’s next growth engine?

(Deutsche Welle) Economists say that things might change in the long run. With India projected to grow more rapidly than China over the next two to three decades, the Indian economy – which will soon boast the world’s largest workforce – is also expected to account for a rising share of global GDP.

(Deutsche Welle) “This will make India a much more important global growth engine for trade and investment flows, particularly with other Asian countries,” said IHS economist Biswas, adding that this would also make India’s voice increasingly important in international policy-making forums such as the G-20, IMF and World Bank.

… India’s economy is far less vulnerable to a Chinese downturn than other Asian economies, as Shang-Jin Wei, chief economist at the Manila-based Asian Development Bank, told DW. “Because Indian firms are less integrated with companies in China and do not sell much to the world market, a Chinese slowdown has limited effect on India,” Wei explained.

Analyst Oliver White agrees. In a recently released paper, the economist at UK-based Fathom Consulting, pointed out that India’s exports accounted for a relatively small proportion of its GDP, at just over 20 percent.

Moreover, India boasts a fairly diversified export base, with its service sector accounting for nearly 50 percent of total exports, thus making the country far less reliant on merchandise trade than other Asian economies. On top of that, the provision of information technology and business outsourcing services is also less likely to be affected by China’s currency depreciation, said White.

… one of the most significant differences between the two countries is not only the quality and depth of infrastructure, but also the fact that China has a much larger industrial economy, whereas India’s economy is domestically driven and therefore needs to significantly strengthen its manufacturing sector to become much more competitive as a global export hub.

And while India aspires to become the world’s next manufacturing powerhouse, it is not clear – given the recent decline in global demand and the fierce opposition to PM Narendra Modi’s economic agenda – whether these plans are feasible anytime soon.

26 August

John Batchelor Show: Gordon Chang, Forbes.com. and Cleo Paskal, Chatham House discuss the evolving geopolitical role of India in light of the ‘crisis’ in China (audio)

27 July

China’s Stock Market Rattles Investors, India Emerges As A Democratic Frontrunner For Business

(Forbes) When China’s Shanghai Composite Index fell over eight percent in a single day, lows unseen since 2007, the impact was felt around the world as Chinese traded stocks in the U.S. also took a hit. The disconcerting volatility has investors fearful that the Chinese government could intervene beyond buying up stocks to stabilize the market and create a less than friendly environment for businesses looking to grow in a weakened economy.

Meanwhile next door in India, things have been looking rosy since China indicated signs of decline. A piece published in The Straits Times called China’s stock market tumbles “a blessing for Indian shareholders” who are reaping benefits from a democratic government busy promoting economic policy reforms, including unification of the country under a single sales tax.

17 July

Sorry, Modi – China Still Doesn’t Take India Seriously

Despite efforts by India’s prime minister, China’s attitudes toward its neighbor have not changed.

(The Diplomat) Not long ago, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi had an apparently successful visit to the People’s Republic of China. In a rare departure from protocol, Chinese President Xi Jinping didn’t receive Modi in Beijing, but his hometown of Xi’an. The highest level of reception was accorded to the Indian prime minister.

On his part, Modi was surprisingly candid. He asserted that there was a need for China to reconsider its approach on some of the issues that hold the two countries back from realizing the full potential of their partnership. As good hosts, the Chinese listened — but like the great terracotta warriors of Xi’an, they stood silent, firm, and resolute.

Diplomatic signals and international activity by the Chinese state since visit signals that for China, it’s business as usual. Beijing has simply ignored Modi’s advice.

4 July

India, China to Discuss Lakhvi Issue and Cooperation on Counterterrorism

China’s willing to talk with India about counter-terrorism cooperation, but will it listen?

On June 23, China blocked an Indian procedural move at the United Nations sanctions committee under resolution 1267 (on Al Qaeda and its affiliates) to question Pakistan over the recent release of Zaki-ur-Rehman Lakhvi, a Lashkar-e-Taiba commander who remains infamous in India for his role as the central planner in the November 2008 terror attacks in Mumbai. China’s move wasn’t its first attempt to shield Pakistan from international scrutiny over its alleged treatment of international terrorists–it had similarly blocked India-initiated procedurals at the United Nations in the past. The Lakhvi episode, however, struck a particular nerve in India given the sensitivity of Lakhvi’s particular case. The issue has escalated to the highest levels of government in India, with Prime Minister Narendra Modi vowing to raise the issue directly with Chinese President Xi Jinping on the sidelines of next week’s BRICS summit in Ufa, Russia.

India and China regularly pay lip service to the issue of collaborating bilaterally on terrorism. In May, Modi and Chinese Premier Li Keqiang stated their joint resolve against terror and “urged all countries and entities to work sincerely to disrupt terrorist networks and their financing, and stop cross-border movement of terrorists.” Despite this, New Delhi and Beijing do not consult on how they will approach these questions at international forums. In the case of Pakistan-backed terror groups, India and China are especially distant.

World Affairs May/June

Caught in the Middle: India, China, and Tibet

While the world accepts Chinese sovereignty over Tibet as a fait accompli, that conquest continues to be destabilizing to the region more than half a century later. When Communist China invaded Tibet, in the 1950s, it acquired a lengthy, ill-defined border with newly independent, democratic India. Soon, India would become host to more than 90,000 Tibetans, the largest population outside Tibet. In addition to the Dalai Lama, India is home to Tibet’s exile government, which completed a democratic transition in 2011. It is now headed by a prime minister and parliament elected by the Tibetan diaspora in South Asia, Europe, and the United States.

The border standoff between India and China, two enormous, nuclear-armed rivals, receives less attention as a potential flash point than the East and South China Seas. Conflicts in those waters could draw in the US, through its alliances with Japan and the Philippines and a defense commitment to Taiwan. However, with the “natural partnership” President Obama and Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi proclaimed during Obama’s unprecedented visit to New Delhi, for India’s National Day, in January 2015, the border, and Tibet, should receive more attention from Washington.

“When there is relative tranquility in Tibet, India and China have reasonably good relations,” writes C. Raja Mohan, an Indian strategist. “When Sino-Tibetan tensions rise, India’s relationship with China heads south.” Under what Mohan calls this “iron law” of Sino-Indian ties, tensions are sure to rise in the years to come.

12 May

C Uday Bhaskar: Engage the Chinese Dragon With The Two Ts

(The Quint) Prime Minister Narendra Modi will be visiting China for his first substantive bilateral engagement with President Xi Jinping about 10 days before he completes one year in office (May 25). It would be by far his most important foreign policy visit.

From the Indian perspective, while there are many economic-trade-investment and connectivity possibilities that need to be enhanced, two Ts, namely Territorial dispute and Terrorism concerns warrant candid high-level political review if the Modi visit is to be meaningful.

Yes, India and China have many areas of mutual benefit ranging from increasing trade and economic cooperation to investment and macro-connectivity projects such as the ambitious Xi led Belt and Road initiative. But all of this will remain stunted and restricted by the glass-ceiling of the strategic and security dissonance represented by the two Ts.

The often heralded Asian century will remain elusive if the continent’s two largest powers are unable to harmonise their anxieties and aspirations. India has a huge domestic development challenge and has to eradicate colossal poverty in the manner that China has – but through the democratic dispensation. The good news is that India is now on an upward trajectory of its GDP with a demographic advantage, and China can be a valuable partner in sustaining this endeavour.

8 May

India and Asian Leadership

Sixty years ago, India was at the forefront of efforts to create a new world order. Times have changed.

By Jayshree Borah

(The Diplomat) As at Bandung 60 years ago, the rhetoric about creating a new Asia-centric world order was a catchphrase of Bandung 2015. However, the difference is that 60 years ago India was at the forefront of efforts to build that world order and now that role is very much being played by China. Nehru’s vision of India as a torchbearer of Asia has long been discarded. Although, India’s Foreign Minister Sushma Swaraj called for the reform of Bretton Woods institutions such as the IMF and World Bank and promised to build a trade route through the Indian Ocean, China is actually way ahead in creating a new economic order with Xi’s “One Belt, One Road” project. Most of the African and Asian countries that attended the summit are already closely linked to China on the economic front, through the Silk Road Economic Belt and 21st-Century Maritime Silk Road, international trade and infrastructure projects. China proposed the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), which appears designed to serve as a substitute for the Bretton Woods institutions. At the end of the summit, participating countries also welcomed Xi’s initiative to provide 100,000 training positions to citizens of developing Asian and African countries over a five-year period, and to hold annual gatherings in China for youths from Asia and Africa.

(The Diplomat) As at Bandung 60 years ago, the rhetoric about creating a new Asia-centric world order was a catchphrase of Bandung 2015. However, the difference is that 60 years ago India was at the forefront of efforts to build that world order and now that role is very much being played by China. Nehru’s vision of India as a torchbearer of Asia has long been discarded. Although, India’s Foreign Minister Sushma Swaraj called for the reform of Bretton Woods institutions such as the IMF and World Bank and promised to build a trade route through the Indian Ocean, China is actually way ahead in creating a new economic order with Xi’s “One Belt, One Road” project. Most of the African and Asian countries that attended the summit are already closely linked to China on the economic front, through the Silk Road Economic Belt and 21st-Century Maritime Silk Road, international trade and infrastructure projects. China proposed the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), which appears designed to serve as a substitute for the Bretton Woods institutions. At the end of the summit, participating countries also welcomed Xi’s initiative to provide 100,000 training positions to citizens of developing Asian and African countries over a five-year period, and to hold annual gatherings in China for youths from Asia and Africa.

16 April

Beyond 1962 — How to Upgrade the Sino-Indian Relationship

To move forward, however, the leaders need to deal with more recent history. This means encouraging creative thinking to alleviate the border dispute, eliminating bureaucratic hurdles to the bilateral business relationship and, above all, working to improve attitudes on both sides through academic exchange and people-to-people contact. The obstacles may be formidable, but the outcomes will be critical to regional—and global—geopolitics.

(Foreign Affairs) India’s increasingly prominent global role—especially through the BRICS group and the G20—has given it a more serious spot on Beijing’s geopolitical map. The countries are both weary of Western-dominated international institutions and India has featured prominently in China’s efforts to build alternatives: the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, the BRICS Bank, and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization. Most recently, Narendra Modi has raised eyebrows in Beijing by courting the United States, Australia, and—especially—Japan. But there’s still a long way to go before China considers India a peer. As Zhu Feng, a leading Chinese commentator and professor at Nanjing University, put it, “We don’t consider India a very successful contender and I don’t think Modi can change that.” …

Perhaps the largest obstacles to a burgeoning relationship are the Chinese and Indian people themselves. The Chinese and Indian publics do not know each other well—and what they do know is colored by historical baggage. This, combined with strong nationalist strands in both countries, makes it difficult for the political relationship to progress. …

At a deeper level, the two societies simply aren’t very appealing to each other. Most Chinese have never eaten Indian food or watched a Bollywood movie and give India little credit for founding China’s largest religion, Buddhism. Many have tried Yoga (which, in China, boasts an estimated 10 million regular practitioners), but consume it largely as an import from the West. And, for a population just one generation removed from near-universal poverty, Western celebrations of India’s mystical asceticism hold little appeal. China doesn’t fare much better in India, where, despite the conspicuous success of Chinese food, few other aspects of China’s ancient or modern culture resonate. The countries’ academics and experts are also poorly placed to teach mutual understanding. China has produced a handful of experts on Indian languages and literature but few experts on Indian politics or economics.

9 February

Catching the dragon

India’s economy is now growing faster than China’s

(The Economist) IN RECENT weeks, economists at the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund and Goldman Sachs, a bank, have tentatively suggested that within a year or two, India’s economy might be growing more quickly than China’s. The day came sooner than they had imagined. Official statistics published on February 9th revealed that India’s GDP rose by 7.5% in 2014, a shade faster than China’s economy managed over the same period (see chart). Narendra Modi, India’s publicity-savvy prime minister, could scarcely have hoped for a better endorsement of his first few months in office.

India has been a rare bright spot among emerging markets. Mr Modi’s pro-growth government won a healthy mandate in elections last May and after a slow start, it has pursued its reform agenda more urgently in recent weeks. The stockmarket has boomed, in part because foreign investors remain keen buyers of Indian assets, even as they pull money from other emerging economies. The rupee is firm. The central bank has even expanded its foreign-exchange reserves to a record $330 billion—thus keeping the rupee from rising by more.

The economy is likely to pick up further. The recent falls in commodity prices, which have hurt raw-material exporters such as Brazil, Russia and South Africa, are a boon for India, which imports 80% of the oil it consumes. Rich economies may fret about the dangers of falling prices around the world; Indians, on the other hand, are pleased they no longer have double-digit inflation at home.

2014

2 December

Rattled by Chinese submarines, India joins other nations in rebuilding fleet

(Reuters) – India is speeding up a navy modernization program and leaning on its neighbors to curb Chinese submarine activity in the Indian Ocean, as nations in the region become increasingly jittery over Beijing’s growing undersea prowess.

Just months after a stand-off along the disputed border dividing India and China in the Himalayas, Chinese submarines have shown up in Sri Lanka, the island nation off India’s southern coast. China has also strengthened ties with the Maldives, the Indian Ocean archipelago.

China’s moves reflect its determination to beef up its presence in the Indian Ocean, through which four-fifths of its oil imports pass, and coincides with escalating tension in the disputed South China Sea.

The country’s first indigenously built nuclear submarine – loaded with nuclear-tipped missiles and headed for sea trials this month – joins the fleet in late 2016. In the meantime, India is in talks with Russia to lease a second nuclear-propelled submarine, navy officials told Reuters.

The government has already turned to industrial group Larsen & Toubro Ltd, which built the hull for the first submarine, to manufacture two more nuclear submarines, sources with knowledge of the matter said.

Elsewhere in the region, Australia is planning to buy up to 12 stealth submarines from Japan, while Vietnam plans to acquire as many as four additional Kilo-class submarines to add to its current fleet of two. Taiwan is seeking U.S. technology to build up its own submarine fleet.

Japan, locked in a dispute with China over islands claimed by both nations, is increasing its fleet of diesel-electric attack submarines to 22 from 16 over the next decade or so.

15 September

C. Uday Bhaskar: China’s WMD cooperation with Pakistan looms over Xi-Modi talks

(Reuters) The visit of Chinese President Xi Jinping to India and his meeting with Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi this week has elicited considerable positive interest in both countries. It has the potential to recast the uneasy Asian strategic framework, and by extension the relations of emerging global powers that are currently clouded by acrimony and mutual mistrust.

… the more nettlesome issue that lies at the core of the current anxiety and suspicion in India about China’s true intent is the opaque Sino-Pakistan nuclear weapon and missile cooperation. Shrouded in secrecy, this WMD (weapons of mass destruction) cooperation goes back to the late 1980’s and most domain experts are familiar with the empirical facts of the issue.

14 September

Xi to Abe, $35 billion is peanuts

The total investment slated to be approved during the 17-19 September visit will exceed $200 billion, thereby dwarfing Japan’s commitment of $35 billion spread over five years.

(Sunday Guardian) Bringing with him as many as eight ministers and 130 top businesspersons from both the public as well as the private sectors, President Xi Jinping of China expects to build on the rapport established with Prime Minister Narendra Modi at the BRICS summit in Brazil to create a new paradigm for the Sino-Indian relationship, according to senior officials contacted on telephone and in person. President Xi touches down in Ahmedabad on 17 September after lightning visits to Maldives and Sri Lanka, and is expected to be welcomed by Prime Minister Modi himself, in the same way as the PM was welcomed in Kyoto by Japan’s PM Shinzo Abe. “President Xi is very keen on seeing for himself the way in which Modi has transformed Gujarat, which is why he was particular to begin his visit in that state”, a top official revealed, adding that “both Xi as well as Modi have a shared interest in unlocking the potential in cooperative relations between China and India”.

30 August

Modi, Abe bid to break China monopoly in rare earths

Because of its near-monopoly over the commercial production of rare earths, China is in a position to deny countries access to rare earths, thereby severely affecting the production of high-technology items. Since Hu Jintao took over as President more than a decade back, China has adopted a dual policy of, (a) seeking to itself make high-tech items rather than simply provide the raw materials for other countries to do so; and (b) capture rare earths deposits, especially in Africa, through commercial deals in countries such as South Africa and Malawi.

8 January

For the better part of three millennia, China and India have developed independently, intersecting only at the rarest of moments across a divide of some of the world’s most forbidding geography. Today, they rank as the world’s first and second most populous nations, but with political, social, and economic systems that place them sharply at odds—most recently along the Arunachal Pradesh border, a hotly contested stretch of the eastern Himalayas. In our winter issue, World Policy Journal calls on writers on both sides of the frontier to assess the interactions and the frictions between these two nations, and their fallout among their smaller and more fragile neighbors—from Bhutan and Nepal to Myanmar, newly opening to the world around it. A leading Indian writer examines the centrally planned and managed nation controlled by a single political party that has seen an economic explosion of activity and growth north of the Himalayas. A top Chinese journalist, who has traveled widely, explores her neighbor to the south, a vibrant, if often cacophonous, multi-party democratic nation that has broken out of its long lethargy to assume a leadership role in technology and innovation. In this second of our annual issues spotlighting a different region of the world, we turn our attention to Asia, and specifically to China and India—a faceoff of monumental proportions engaging the entire region and capturing the attention of much of the world—and seek to unwrap some effective means of navigating their still fraught relationship. ( World Policy Journal Winter 2013/14)

The Big Question: Which Country Will Emerge As the Leading Power?

China and India each have a legitimate claim to hegemony, to leadership, and to a shared or competitive future. We asked our panel of global experts which nation might emerge as Asia’s leading power in the future.

Map Room: Water Woes

Asia’s water resources are coming under increasing stress. World Policy Journal examines three areas where competition over water resources is creating the greatest potential for Sino-Indian conflict, while showcasing the methods China and India are employing to secure their future water reserves along three contentious rivers.

India Through Chinese Eyes

Despite its size, economic clout, and geographic proximity to China, India remains a blind spot in China’s foreign policy and among most Chinese. China’s criticism of India’s dysfunctional democracy, along with a lack of cultural awareness, perpetuates a state of political and diplomatic imbalance between the two neighbors. With the governments’ designated Year of Friendship and Exchange slated for 2014, Li Xin reveals why China would benefit from building a closer, multi-dimensional relationship with India.

Anatomy: Highway to Higher Education

The two leading universities in China and India, Peking University and IIT-Bombay respectively, represent two vastly different approaches to education and life. World Policy Journal delves into these differences. Though each requires students to take highly competitive exams, Peking University offers students an array of subjects to study, while IIT-Bombay immediately places students on a science and engineering track. After graduation, Chinese students remain in the country, while Indian students apply for work visas abroad at strikingly high rates.

China Through Indian Eyes

At odds for the last 50 years, India and China share little in common except for a border. Despite fundamental differences in work culture, social structure, and political ideology, Nazia Vasi reveals how globalization and cross-cultural interactions are shaping and potentially strengthening Indians’ interaction with their Chinese counterparts.

Timeline: 1959-Present

To understand the modern trajectory of Sino-Indian relations, World Policy Journal has focused on turning points that have come to define the two countries’ shared history. Beginning at a pivotal moment—the 1959 Tibetan Rising—we march through decades of military struggles and political confrontations to present-day diplomatic and economic negotiations, which bode well for building confidence and trust between Asia’s two superpowers.

One Comment on "China and India 2014-July 2020"

A European observer comments:

My own feelings are mainly influenced by my discussions with Mountbatten and Lee Kuan-Yew, both ages ago.

There are certain things which I feel to be strongly in India’s favor:

It is a democracy with free elections

India has an independent judiciary

India’s policies are (not counting Kashmir) non-imperialistic

Both nations are suffering from rampant corruption

According to late Lee Kuan-Yew:

China will sooner or later disintegrate because of her history. The Chinese are inherently deeply distrustful towards a central administration.

China’s policies are overtly imperialistic and alienate her neighbors.. China is seen by the outside world as a belligerent nation.

For the Chinese everything is about money, money and power. There is nothing else of value in life.

The peoples of India have other values too.