Re Ian Bremmer 'Could third-party candidates upend the 2024 US election?' 3 April The current political movement in the USA…

The Partition of India 70th anniversary

Written by Diana Thebaud Nicholson // August 14, 2017 // Government & Governance, India, Pakistan // Comments Off on The Partition of India 70th anniversary

Partition, 70 years on: Salman Rushdie, Kamila Shamsie and other writers reflect

More than a million were killed and many millions more displaced by Indian partition. Authors consider its bloody legacy and the crises now facing their countries

Pankaj Mishra: To think about partition on its 70th anniversary is to think, unavoidably, about the extraordinary crisis in India today. The 50th and 60th anniversaries of one of the 20th century’s biggest calamities were leavened with the possibility that India, liberal-democratic, secular and energetically globalising, was finally achieving the greatness its famous leaders had promised. In contrast to India’s grand and imminent tryst with destiny, Pakistan’s fate seemed to be obsessive self-harm.

The celebrations of a “rising” India were not much muted in 1997 and 2007, even as hands were dutifully wrung about the imperialist skulduggery and savage ethnic cleansing that founded the nation states of India and Pakistan, defined their self-images and condemned them to permanent internal and external conflict. Today, as the portrait of a co-conspirator in the assassination of Mahatma Gandhi hangs in the Indian parliament, it is the scale and ferocity of India’s mutation that haunts our thoughts.

… My own life has been enriched by Pakistani writers, musicians, cricketers and friendships across borders. Yet the Hindu fanatic who murdered Gandhi for being soft on Muslims and Pakistan exemplified early the lethal logic of nation-building. So did many avowedly secular Indian leaders who used brute force to hold on to Kashmir. (The Guardian, 5 August)

Modi calls for ‘new India’ as country celebrates 70 years of independence

By Huizhong Wu, Omar Khan and Manveena Suri

(CNN) Crowds gathered at Delhi’s historic Red Fort on Tuesday to hear Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi speak on the 70th anniversary of Indian independence from British rule.

Modi marked the occasion by asking Indians to set aside their differences to help rid the country of long-standing social ills such as class prejudice and corruption.

“India is about peace, unity and goodwill,” said Modi. “We have to take the country ahead with the determination of creating a new India.”

In Modi’s new India, the country’s youthful population will keep up with changes in the global economy, villages will have electricity and “the poor will have concrete houses with water,” said the Prime Minister, referring to some of his administration’s major projects in the last three years.

14 August

Happy 70th anniversary, Pakistan

By Shahid M Amin, Pakistan’s former Ambassador to Saudi Arabia, Soviet Union, France, Nigeria and Libya.

(Pakistan Observer) There have been immense challenges and grave threats, but we have survived. We have made many mistakes; we have erred from the path laid out by the Quaid-i-Azam; we have not been fortunate with the leaders we have had; some of them have plundered the country. It is right that we should make honest appraisals, provided we do not dwell only on the negative. Yes, we should learn from our mistakes and always seek to improve ourselves. But there has been an unfortunate trend to be overly critical of Pakistan. Our media tends to play up the negative —the bomb explosions and target killings— as if this is the way of life in Pakistan. A comparison of crime figures suggests that many big cities in the West have greater mortality rates due to crime and terrorism than Pakistani cities like Karachi. Our poor image abroad is partially due to our own negativity. Some of us suffer from an inferiority complex and some have a political axe to grind. Our enemies are, of course, always out to tar Pakistan’s image.

Let us look at some positives. Pakistan today is one of the strongest military powers in the world and the only Muslim state with nuclear weapons and delivery system. Our agricultural production since independence has quadrupled. We had little industry in 1947 and today have a large industrial base. Per capita income has gone up significantly. Literacy has increased and the number of universities has risen from one to over seventy. Pakistani women are working in all sectors, including the armed forces. The media has advanced beyond comparison. We have more political freedom than so many countries. I spent forty years in the diplomatic service and visited countries all over the world and can say in all honesty that we in Pakistan are so much better off than people in many of those states.

‘At the Stroke of Midnight My Entire Family Was Displaced’

(NYT) August marks the 70th anniversary of the end of British colonial rule in India and the creation of the two independent countries of India and Pakistan, carved along religious and political lines. More than 10 million people were uprooted. We asked readers how they or their families were affected. These are some of their stories.

13 August

Enduring the effects of partition in Kashmir

Seven decades on, the Indian Partition continues to haunt the Kashmir Valley.

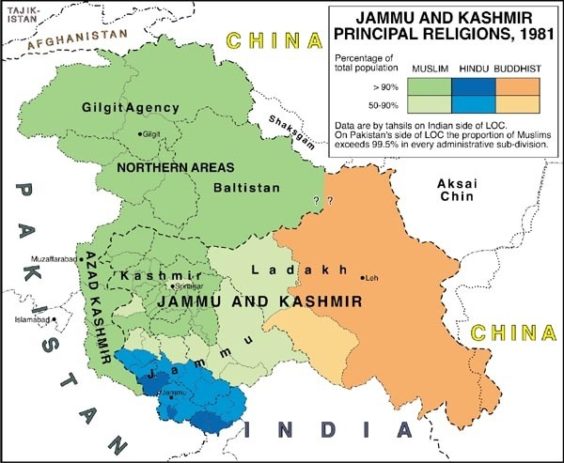

(Al Jazeera) As the 70th anniversary of the partition of Indian subcontinent approaches, for some of the communities torn apart by the aftermath of the historic event, the effects of the trauma still linger. The Kashmir region was among the communities divided in a violent skirmish between the newly emancipated India and Pakistan. Both countries now administer parts of Kashmir, but both claim rights over the entire territory.

In Indian-administered Kashmir, the predominantly Muslim population harbour strong sentiments against Indian rule and an estimated 70,000 people have been killed in the violence that has persisted since an armed movement of resistance against Indian rule broke out in the region in the aftermath the disputed state election of 1987.

The armed groups leading this movement of resistance demand that Kashmir be united either under Pakistani rule or as an independent country which the Indian government rejects.

While the ongoing debate over the future of this war-torn region persists, it seldom deviates from the geopolitical aspects of the bilateral dispute dating back to 1947.

Giving Voice To Memories From 1947 Partition And The Birth Of India And Pakistan

(NPR) As India and Pakistan celebrate 70 years of independence this week, the legacy of the August 1947 Partition of British-ruled India that resulted in the birth of these two nations is something both are still coming to terms with.

Religious violence exploded as Hindus and Sikhs fled toward India, and Muslims toward Pakistan, the newly created homeland for South Asia’s Muslims. Millions of people were uprooted and displaced from cities, towns and villages where their families had lived for generations.

It was the largest mass migration of the 20th century. Over the course of a year, an estimated 15 million people crossed borders that were drawn up in haste by the British Empire.

Only in recent years have the memories and insights of those who lived through the trauma and chaos of Partition been recorded in a systematic way. For such a central and defining set of events in both India and Pakistan, the stories of Partition witnesses and survivors were, for the most part, not given voice outside their own families.

Guneeta Singh Bhalla is the founder of the 1947 Partition Archive, a nonprofit based in Berkeley, Calif., that is highlighting the stories and honoring the memories of those who lived through Partition.

Independence: Do Indians care about the British any more?

Seventy years since India gained its independence from the British Empire, the UK is seeking a closer trading relationship. But what do modern Indians think about the British?

(BBC News Magazine) What India thinks of us is arguably more important now than ever before, given how much the British government is pinning on our future relationship with this vast and increasingly mighty nation.

Theresa May chose India as her first major overseas visit as prime minister very deliberately. As Britain looks towards its post-Brexit future, it is reaching out to India for support.

[Former UN under-secretary general] Shashi Tharoor is perhaps the most vocal and potent critic of Britain’s imperial legacy around today.

A speech he made at the Oxford Union in 2015 demanding Britain atone for its wrongs in India became a social media sensation.

The impact of his address persuaded him to write a book, published earlier this year, and – in Britain – called Inglorious Empire.

He felt compelled to write it, he says, because of the “moral urgency of explaining to today’s Indians why colonialism was the horror it turned out to be”.

it is instructive to compare how the 70th anniversary of independence and the partition of India is being reported in India and in Britain.

In India it is not a big story. Yes, the day will be marked by a speech from Prime Minister Narendra Modi at the magnificent Red Fort in the middle of Delhi.

There have been articles and television discussions reflecting on the state of the nation 70 years on, but nothing like the torrent of coverage the event is receiving in the UK.

In Britain newspapers and television programmes will mark the anniversary with big features and special items, while the BBC and other broadcasters have commissioned a raft of documentaries and dramas – even a film.

11 August 2017

The partition goes on: A Pakistani perspective

Pakistani novelist Mohammed Hanif examines the legacy of partition and the ways in which it continues in slow motion.

Twenty years ago I visited India for the first time. We were doing the same thing back then, celebrating 50 years of independence, or mourning 50 years of partition to a steady beating of breasts: why can’t we live like friendly neighbours?

Like many Pakistanis I saw my first Indians in London and was surprised that they were a bit like us. Most Indians and Pakistanis have the same reaction when they meet. It seems as if they are brought up to believe that a community of ferals lives across the border.

My first Indian friend and colleague, Zubair Ahmed, came up with this rather clever idea that we should travel to each other’s country, then come back and put together a series of programmes comparing our reactions. Originally we wanted to go and live with each other’s families but in retrospect, wisely, we decided not to take this newfound brotherhood too far.

6 August

Why Pakistan and India remain in denial 70 years on from partition

The division of British India was poorly planned and brutally carried out, as fear and revenge attacks led to a bloody sectarian ‘cleansing’

(The Guardian) The north-eastern and north-western flanks of the country, made up of Muslim majorities, became Pakistan on 14 August 1947. The rest of the country, predominantly Hindu, but also with large religious minorities peppered throughout, became India. Sandwiched between these areas stood the provinces of Bengal (in the east) and Punjab (in the north-west), densely populated agricultural regions where Muslims, Hindus and Punjabi Sikhs had cultivated the land side by side for generations. The thought of segregating these two regions was so preposterous that few had ever contemplated it, so no preparations had been made for a population exchange.

3 March 2011

The Hidden Story of Partition and its Legacies

The Hidden Story of Partition and its Legacies

(BBC History) India and Pakistan won independence in August 1947, following a nationalist struggle lasting nearly three decades. It set a vital precedent for the negotiated winding up of European empires elsewhere. Unfortunately, it was accompanied by the largest mass migration in human history of some 10 million. As many as one million civilians died in the accompanying riots and local-level fighting, particularly in the western region of Punjab which was cut in two by the border.

The agreement to divide colonial India into two separate states – one with a Muslim majority (Pakistan) and the other with a Hindu majority (India) is commonly seen as the outcome of conflict between the nations’ elites. This explanation, however, renders the mass violence that accompanied partition difficult to explain.

If Pakistan were indeed created as a homeland for Muslims, it is hard to understand why far more were left behind in India than were incorporated into the new state of Pakistan – a state created in two halves, one in the east (formerly East Bengal, now Bangladesh) and the other 1,700 kilometres away on the western side of the subcontinent [see map].

An act of parliament proposed a date for the transfer of power into Indian hands in June 1948, summarily advanced to August 1947 at the whim of the last viceroy, Lord Louis Mountbatten. This left a great many issues and interests unresolved at the end of colonial rule.

In charge of negotiations, the viceroy exacerbated difficulties by focusing largely on Jinnah’s Muslim League and the Indian National Congress (led by Jawaharlal Nehru).

The two parties’ representative status was established by Constituent Assembly elections in July 1946, but fell well short of a universal franchise.

Tellingly, although Pakistan celebrated its independence on 14 August and India on 15 August 1947, the border between the two new states was not announced until 17 August.

28 August 2007

Canada and the Creation of India and Pakistan

(Asia Pacific Foundation) In Ottawa, the ever cautious Prime Minister Mackenzie King, nervously contemplated whether Canada would be drawn into the turbulent political drama of post-partition India as events quickly spiraled out of control and Britain sought support from its Commonwealth colleagues and pondered the future status of India and, to a lesser extent, Pakistan within the Commonwealth. The Canadians concluded that the partitioning of the subcontinent was not necessarily a bad thing, nor should it prevent India and Pakistan from entry into the Commonwealth. Indeed, membership in the Commonwealth, Ottawa mused, might even lessen any difficulties created by partition while improving good relations between the peoples of South Asia and those of the Commonwealth. But King remained worried that Canada might become directly involved with the partition matter.

He recorded in his diary entry of 28 May, 1947 his suspicion that Britain was trying to unload its problems in India onto the Commonwealth and he rebuked those in Cabinet who thought Ottawa might help resolve the partition crisis, “I opened out pretty strongly against pretending to advise on matters that we knew nothing about. I said quite openly that there was not a single member of the Cabinet who was in a position to advise in regard to India, who understood the situation there or realize what implications there might be in tendering advice in matter of this kind. I pointed out that India was a dependency of Britain. She should deal with the matter herself. I thought we ought to help bear burdens that were legitimate, but should not go out of our way to load Canada with obligations that we could not see the beginning or the end of.”

The High Commission was setting up shop just as the magnitude of partition and independence dawned on politicians, diplomats, and the millions of peoples who were affected by the border changes. There was no blueprint to deal with the number of complex issues created by the partition decision such as which states might join India or Pakistan, the setting up of a Boundary Commission to deal with the partition of Punjab and Bengal, or the division of assets of British India, including the army.

As the birth of India and Pakistan took place on midnight August 14 celebrations erupted across New Delhi. From Ottawa, Mackenzie King too revelled in the news of India’s birth as he heard the announcement of India’s independence over the radio. “A great moment in history” King recorded in his Diary, as he contemplated the ‘remarkable’ fate in that he “should have been the one to send Canada’s greetings & good wishes to India & Pakistan.”

Despite the chaos created by partition the decision to recognize India and Pakistan was a crucial step in the evolution of Canadian foreign policy and society. Canada had finally established a diplomatic presence in South Asia that rapidly expanded. In under a decade Canada would play a key role in the creation of a new multiracial commonwealth that included the new states of Pakistan, India, and Ceylon; Ottawa ventured into its first foreign aid foray through the Colombo Plan giving billions in aid to India and Pakistan over the coming decades, and for better or for worse Canada helped India develop its nuclear infrastructure. Perhaps most significantly, immigration from South Asia has steadily increased from 1947 when a rigid quota system tightly restricted immigration to today where South Asians make up the second-largest largest pool of immigrants, rapidly changing the face of urban Canada. But in that turbulent summer of 1947, Canada’s politicians and policymakers, who had absolutely no experience with the Indian subcontinent, were struggling to learn what a newly independent and impoverished India and Pakistan meant for Canada and its allies in the early Cold War era.